babeular juxtapositioning

originally posted: 2023

Today we have a twofer: two postcards advertising ChickClick. In case the name and art didn't make the target audience obvious, this was a late-1990s network of websites aimed at women and teenage girls -- relatively well-documented, as ladysites of the time went, and relatively well-trafficked too. At least one of you reading this has probably just experienced a full-body nostalgia frisson. For the rest of you, here's a deep dive.

First, let's talk about this art. The illustrator, Tiffany Spencer, was with ChickClick either from the beginning or close to it. If you've seen girls' media from the 1990s, or beyond it, you've seen this style: a bit of '70s groovival fashion and color scheme, and a heap of the 1990s' favorite word, "attitude." Spencer's illustrations have made it into at least one academic paper, which situates them among riot grrrl zine covers. What most girls encountered in their lives, though, was the diluted version: the big funded corporate media version. As this 1998 Entertainment Weekly review put it:

"Visually, [both sites] are steeped in what’s come to be the standard grrl aesthetic. Call it barbed wire and bubble gum: an ironic use of pastels and cursive type (don’t forget that send-up of ditz script, an i dotted with a heart) mixed with a few butch effects (guns, knives) and cheesecake illos to symbolize the reappropriation of the objectified female form. Then it’s all trimmed with kinderwhore-meets-Hello Kitty girly garnishes. A skeptic might wonder if this kinda cute, kinda menacing effect doesn’t put a distracting gloss on the sites’ essential feminism. After all, who outside the alterna-culture is likely to take a female over the age of 8 wearing pink barrettes and a plastic Barbie watch all that seriously? But the juxtapositioning gets at the heart of the grrl politic: A woman can be fun and babeular and still be sharp. Like a kitten with a whip. And a T1 line. For all that, a woman over 22 might find the unending whimsy a bit precious." - EW staff blurb, May 1, 1998

So, so many potential subheads in this one paragraph alone. You do, though, get the idea. And the barbed-wire-to-bubble-gum ratio would be diluted further still: Delia's catalogs, Limited Toos and Club Libby Lus. (And the girls were buying; unsurprisingly, each of these brands has since been memorialized online or brought back from the dead to sell to tweens and/or nostalgia-pilled adults.)

You may have noted the plural there: "these sites." There were many; we've covered one here, even. The precursor to ChickClick was called EstroNet -- yes, I know -- which was less a site than a network of what would now be called verticals, then called "zines." (The term was officially short for "web magazines," but was also undoubtedly a nod to the DIY print booklets.) Among them were relatively well-known properties like sassyish/Sassy-ish site gURL, as well as the saucier-named Minx and Wench. Some were independent blogs (sorry, zines); others were funded by Tripod and/or run by New York Times staffers. But the lines between indie and corpo often blurred, as they do.

In 1998, EstroNet merged with an even girlbossier counterpart, ChickClick. (Some sources say 1999, but a New York Times article from 1998 mentioned that the merger had happened "last week.") As usual, news articles of the time generated so much phenomenal quote that I want to include all of them. For instance, here's the founder pitching the site's appeal:

"[The Net] is the perfect medium for teen girls because they don’t need a car to participate. It’s like the phone, but better because they can swap Jpegs." - Heidi Swanson, quoted by Jocelyn Longworth of Kidscreen, July 1, 1999

With this merger came a new set of verticals, of the "riotous" (SFGate's words) variety:

"Everything from Riotgrrl (the site where you can force-feed supermodels either steak or SlimFast), to Disgruntled Housewife, home of the famous Dick List (first names of rotten ex's) to GrrlGamer, where you can play a game that allows you to "frag" (set on fire) a video version of Lara Croft, the sexy heroine (hated by feminists) of the Tomb Raider game." - Jane Ganahl, SFGate, December 24, 1998

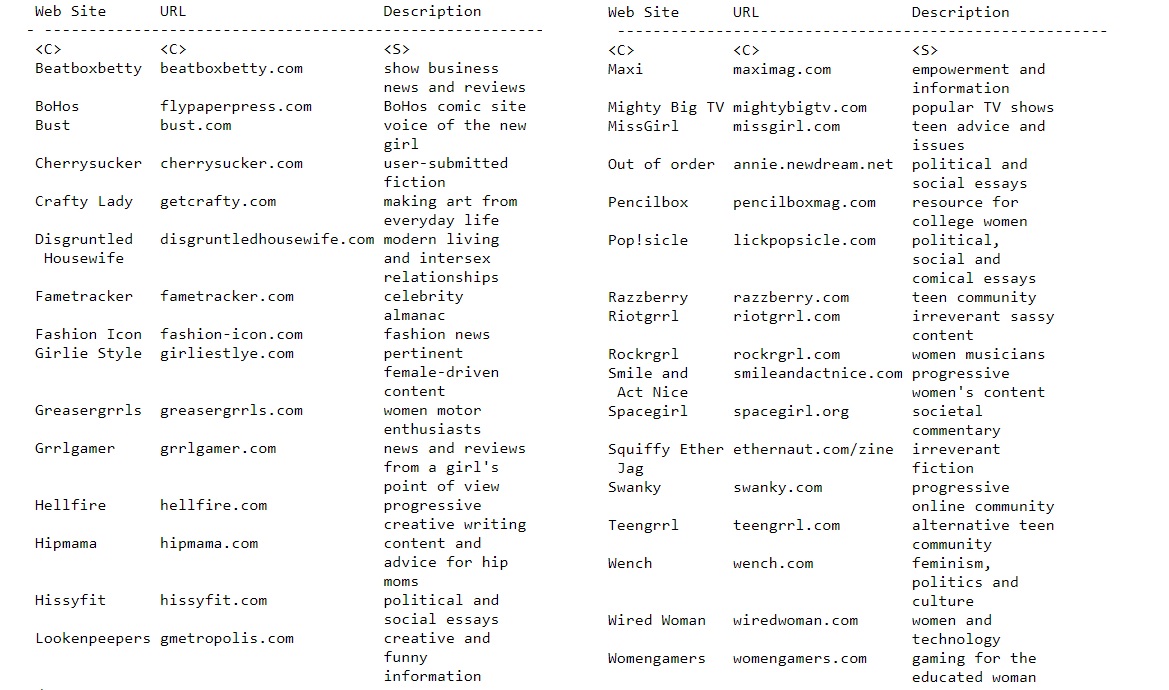

This is a very partial list of the dozens of verticals that the site would grow to encompass. Several more affiliated websites are listed in a SEC filing about ChickClick and its owners. (Why a SEC filing? We'll get to that.)

These sites largely targeted a middle-to-upper-class white audience, despite the usual cursory attempts to broaden their purview. They were less feminist than feminish, though the frank sexual content nevertheless provoked the religious right probably even more than it was mean to. But an editorial throughline did form, one familiar to blog readers of the '10s: The homepage aggregated links from over the transom, often with snarky commentary, on the homepage. "A feature on the front-page there was worth all the web kudos in the world," wrote one memorial.

News coverage talked up ChickClick's reportedly scrappy origins -- see this MediaWeek piece, which delightfully calls the site a "seat-of-the-lace-pants operation." But here, too, connections and money were very much involved. Though the individual sites made generally about "four figures" each in the beginning, according to MediaWeek, the network's pageviews were in the many millions, and ad deals were made with companies as major as Esprit, Procter & Gamble and Netscape. And big web publishing names were involved from the start: The site was founded when designer Heidi Swanson pitched the idea to Chris Anderson, the president of Imagine Media -- better known these days as IGN. (Anderson would go on to curate TED Talks; Swanson now writes vegetarian cookbooks.)

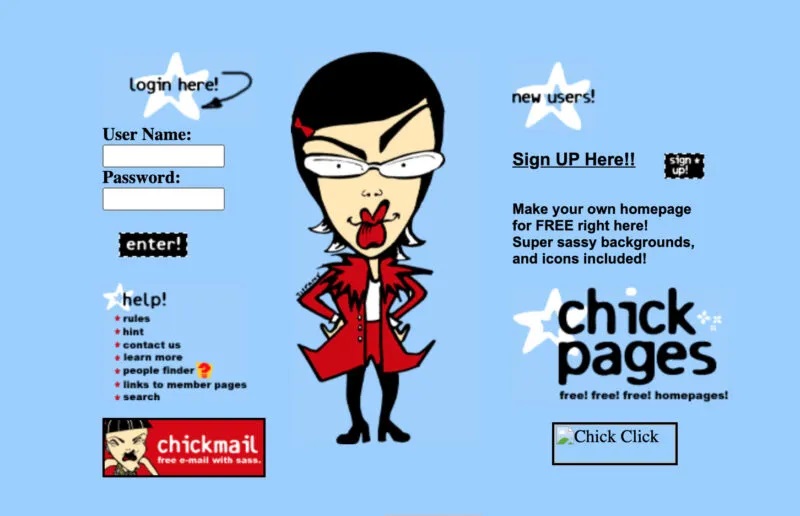

With money and fame, as always, came pivots. There were forums and chatrooms. There was a streaming and syndicated radio program ChickClickradio, whose cohosting DJ Michelle Madden would later write for similarly sassy Jane and other publications (plus do research for Being John Malkovich and Adaptation) The station played mostly Top 40, but there was also a Lilith Fair sponsorship. There was an e-commerce arm. There was an email service and a web host that, regrettably, was not called "Sheocities":

The rest of the story is dully familiar, a tale of the same enshittifying rot that overcome dotcom startups and media properties by the hundreds. Imagine Media's online publications were shunted between a couple of spin-offs and sell-offs: first the ultra-generically named Affiliation Networks, then Snowball. Their pitch was to embody their name in Katamari fashion, and is kind of amazing in a stupid Y2K way:

Snowball (dot) com, which spun out of Imagine Media last February, wants to be the No. 1 destination in cyberspace for young people living the fully wired lifestyle. ... Each network consists of a collection of independently owned sites that link to a central hub site and share advertising operations. Each is tailored to reach a distinct demographic stripe within a group Snowball calls "Generation i," loosely defined as 12- to 29-year-olds who are highly acclimated to on-line culture.

Snowball would expand upon this fetching, never-before-captured demographic stripe in their later IPO:

Generation i is a large Internet audience that desires community, entertainment and content focused on their particular needs. Because this generation is accustomed to numerous cable television channels and a wealth of entertainment choices, its members expect a wide range of specialized content that is available on demand. ... The content created by our editorial staff, affiliates, and the network users is edited and organized into networks to create a strong and consistent voice directed at Generation i. Our networks also promote the community participation and personal growth of Generation i users by encouraging communication among users, and between users and network editors, through message boards, chat sessions, instant messaging and email.

Despite the evident concern about millennials' personal growth, this is not exactly what happened. The site got private equity funding, went public in 2000, and crashed shortly after. ChickClick was shut down in 2002, its community scattering to various Livejournals and Ultimate Bulletin Boards forums. Lessons were not learned -- except perhaps the lesson to never call anyone "generation i" again.

What this all reminds me of, distinctly, is that period in the mid-2010s with its own spate of women's sites -- Jezebel, XOJane, The Hairpin, The Toast, Bustle, and more I'm sure I'm forgetting -- and its own demise. Then, as now, a spate of sites grew an audience of extremely online young women, fostering "community participation and personal growth" but also more internal and external tension and trolling than the promotions and eulogies acknowledged (with some exceptions), producing in-depth reporting along with zippy snark but ever beholden to ad money and funding, presenting as institutions but being inevitably shuttered or, worse, decaying into AI slop troughs. A 2000 postmortem piece in Salon called "What happened to the women's web?, despite a few now-anachronistic "see, Barbie, girls CAN use technology!" quips, could have been written today:

There's a reason why Women (dot) com these days seems to be so heavy on astrology and sex tips: It's because these are far and away the most popular features, despite Women (dot) com's more thoughtful political and business coverage. 'The reality is that the bread and butter of page views comes from sex and horoscopes -- it's the dirty little secret of any woman's site that that's where the traffic is,' says a former Women (dot) com editor. And to make matters worse, she says, 'page views are put aside for beauty because that's where the advertisers were.'

footnotes

- Given the decades-removed, only partially archived reporting and murky merger timeline, I'm not totally sure which verticals originally belonged to which site. 🔼

- "Web kudos" is a much nicer metaphor than "virality." Let's bring it back. 🔼

- The association was somewhat short-lived; this IGN history mentions, in a very hoo-boy aside, that the site's offices "were quickly moved away from those of the IGN editors for reasons too numerous to mention." 🔼

- From the same IGN history: "'I was home sick that day, and I called Mark Jung at the office to ask him if he knew what that word meant in the vernacular,' says Tal Blevins, now IGN's vice president of games content. 'I played the clip from Clerks onto his voicemail.'" 🔼

- or, as they're known today, extremely online millennials 🔼

- note: Salon was a much different, less clickbaity site in 2000 🔼

return to blog index, or return home (or: want your own postcard?)